[edit]

Management of Nosocomial (Hospital-Acquired) Infections of SARS-CoV2

Prepared for the DELVE Initiative by

Citation

(2020), Management of Nosocomial (Hospital-Acquired) Infections of SARS-CoV2. DELVE Addendum NOS-TD2. Published 06 July 2020. Available from https://rs-delve.github.io/addenda/2020/07/06/management-of-nosocomial-infections-of-sars-cov2.html.

- Background

- Summary

- UK government’s COVID-19 Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines

- SARS-CoV-2 Infection prevention and control measures in South Korea, Singapore, New Zealand, Ireland and Australia 22

- Footnotes and References

1. Background

The risk of nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV 2 has made health workers around the world extremely vulnerable to infection and mortality. While there are no formal estimates of nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2, high infection rates among health-care workers (HCWs) highlights just how widespread this problem is globally as well as in the UK. Based on data from 30 countries from national nursing associations, government figures and media reports, the International Council of Nurses has reported that at least 90,000 health-care workers worldwide are believed to have been infected with SARS-CoV 2.1 In early May, UK government figures2 reported an infection rate of 4.8% among health, social care and essential workers and their households. However, Henegan and colleagues estimated that 30.5% of all infected cases on the 16th of April were related to healthcare workers, and also discussing the difficulty in gaining accurate estimates of infection rates among health workers alone.3 As of April 22, Cook and colleagues reported that a total of 116 NHS staff had died from SARS-CoV 2; and 63% of the cases were of the BAME communities.4

Figures from China’s National Health Commission show that more than 3300 health-care workers (4% of the 81,285 reported infections) have been infected as of early March.5 Other reports from China have reported an infection rate of 2.09-29% among healthcare workers.678 In May, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control reported that 20% of SARS-CoV 2 cases in Spain are healthcare workers, compared with 10% in Italy as a whole (in the hard-hit region of Lombardy the percentage rises to 20%). In Germany, as of May 16, 11,780 cases with a SARS-CoV-2 infection have been notified among staff working in medical facilities (6.7% of total cases i.e. 173,772).9 In the United States, infected healthcare workers represent 11% of total cases.10

The nosocomial route of transmission amplifies infections among health workers as well as patients coming to hospital settings for other medical reasons, thus making infection control and management practices a critical component of a government’s response for containing SARS-CoV

- This report provides a scoping review of how countries have prevented and managed nosocomial SARS-CoV 2 infections. This review covered 11 countries including the UK, South Korea, Singapore, New Zealand, Ireland, Australia, Germany, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, and relied on guidelines from government websites, peer-reviewed articles and news media reports.

2. Summary

What are the guidelines and practices in the UK?

See Section 3 for detailed guidelines and references.

-

Point of entry: Symptomatic individuals or those suspected with SARS-CoV-2 symptoms must contact the NHS via a helpline or online for advice on hospital admission. At the point of entry, patients must be identified as asymptomatic, symptomatic for COVID-19 or COVID+. All patients should be tested on emergency admission.

-

Separation among zones of risk: Guidelines state that patients with suspected/possible COVID-19 need to be segregated, especially in admission/waiting and non-COVID areas. Confirmed/suspected cases must be isolated in separate room or a COVID+ cohorted area. Several NHS hospitals have divided their facility into two zones: (i) SARS-CoV-2 (positive and suspected cases) and (ii) Non-SARS-CoV-2.

-

Use of masks: Guidelines state that symptomatic patients may wear masks, but this is not mandated. From 2 April, all healthcare facilities were recommended to wear masks for all contact with all patients and symptomatic patients were recommended to wear masks if able to do so. As of 15 June, all healthcare workers will have to wear surgical masks in all areas of the hospital while visitors will have to wear face coverings at all times.

-

Personal protective equipment (PPE): Healthcare workers are recommended to wear PPE including gloves, disposable apron or gown (based on risk assessment), surgical masks or fluid resistant mask or filtering face piece respirator (based on risk of procedure i.e. aerosol generating procedures) and face and eye protection. It is important to note, that when providing care to any individuals in the extremely vulnerable group undergoing shielding, HCWs have to wear gloves, disposable plastic apron and surgical mask.

-

Teams: It is recommended that when there are sufficient levels of staff, a dedicated team of staff should be assigned to care for patients in isolation/cohort rooms/areas and there should be efforts to reduce staff movement between pathways for SARS-CoV-2 and non-SARS-CoV-2.

-

Testing for HCWs: Symptomatic HCWs need to inform their employer and can get tested within the first three days of the onset of symptoms. If test result is negative, staff can resume patient care. On a positive test result, staff can resume patient care after 7 days if symptoms have resolved. While guidelines recommend the testing of asymptomatic staff based on available capacity, NHS hospitals11 (Newcastle Upon Tyne, Sheffield, Cambridge, Imperial and Barts Health NHS Trust London) have started testing asymptomatic staff, part of pilot studies.

-

Testing for patients: Between 17th March and 15th April, around 25,000 people were discharged from hospitals into care homes. Due to government policy at the time, not all patients were tested for COVID-19 before discharge, with priority given to patients with symptoms.12 13 On 15 April, the policy was changed to test all those being discharged into care homes and all elective admissions.

-

Visitors: Visiting may be suspended if considered appropriate depending on local circumstances and risk assessment. Also, visitors with symptoms cannot enter the hospital.

-

Non-SARS-CoV-2 services: All opportunities for remote, multi-professional virtual consultations must be maximised. On 27 April, the government announced that the “restoration of other NHS services” will start from 28 April on a “hospital-by-hospital” basis. As of 14 May, NHS England stated that ‘over the coming weeks patients who need important planned procedures – including surgery – will begin to be scheduled for that care, with specialists prioritising those with the most urgent clinical need.

What are the approaches followed by other countries?

See Section 4 for detailed guidelines and references.

Countries use an ecosystem of measures to prevent and manage SARS-CoV 2 infections among patients and healthcare workers in the hospital setting. All patients are screened at the point of entry and then suspected cases with respiratory symptoms are allocated to separate wards and clinics, in separate locations, with separate teams. In countries such as South Korea, Singapore, Denmark, and recently Italy, individuals are screened through community based testing and primary healthcare staff (GPs) and only then sent to hospitals if presenting with severe symptoms, thereby reducing the burden on staff for initial triage at the point of entry. In Ireland, symptomatic patients are screened in a triage tent at the entrance of the emergency department. Patients have to wear surgical masks, and health-care workers have to wear personal protective equipment based on the risk level of patient interaction. Disinfecting areas for reducing environmental transmission and physical distancing measures are observed. Visitors and caregivers are restricted entry to hospitals in most countries. Finally, health staff are encouraged to shift to virtual channels like telephone or video consultations for other non-COVID-19 services as much as possible.

Countries have adopted several measures to reduce the risk of infection among HCW.

-

Personal protective equipment (PPE): PPE is commonly recommended across all the reviewed countries. All HCWs have to wear surgical masks during patient interactions, and then based on the risk level of the task around patient care (i.e. routine care or aerosol generating procedures), they have to put on a lower or higher level of PPE. While donning appropriate levels of PPE is a universally recommended measure, reports from Italy and Spain,14 highlighted the shortages in PPE which has affected healthcare workers.

-

Organisational practices: Some countries follow organisational practices such as allocating designated and small teams for treating COVID-19 and non COVID-19 patients. This practice prevents cross-integration of staff between clean and infected wards, and with small dedicated teams it also becomes easy to do contact tracing if members get infected. In South Korea’s Samsung Medical Centre,15 COVID-19 units are staffed by only dedicated core clinical teams with special training who live in hospital accommodations during two-week shifts and then are quarantined for one week and only allowed to return to the care of non COVID-19 patients after a negative COVID-19 test.

-

Testing: All the countries provided testing for HCWs on presentation of SARS-CoV2 symptoms. For HCWs in Singapore, temperature is monitored twice every day and with any increase in temperature, HCWs are evaluated for testing. While Italy and Norway require HCWs to present with severe symptoms for testing, other countries tested even with mild symptoms. Testing alone is not enough. It is also important to ensure that HCWs are quarantined or allowed to rest well before they resume patient care. Countries follow different strategies after a HCW tests positive. In Singapore,16 when someone (health-care worker, staff or patient) in the hospital tests positive, response teams trace every contact and then quarantine only those who had close contact with the infected person, and close contact is defined as spending 30 minutes at a distance of less than six feet and without the use of a surgical mask. If the exposure is shorter than the prescribed limit but within six feet for more than two minutes, workers can stay on the job if they wear a surgical mask and have twice-daily temperature checks. People who have had brief, incidental contact are just asked to monitor themselves for symptoms. In Germany,17 if HCWs have SARS-CoV2, they cannot care for patients and can resume work only after 48 hours of being free from symptoms and after negative PCR from 2 simultaneous oro- and nasopharyngeal swabs. As of mid-May, Vietnam,18 has started conducting weekly testing for all its HCWs in the hospital setting.

Support mechanisms: Singapore and Denmark have set up peer support networks and psychological interventions for its HCW to address the physical fatigue and psychological stress of donning PPE and working in COVID-19 shifts.

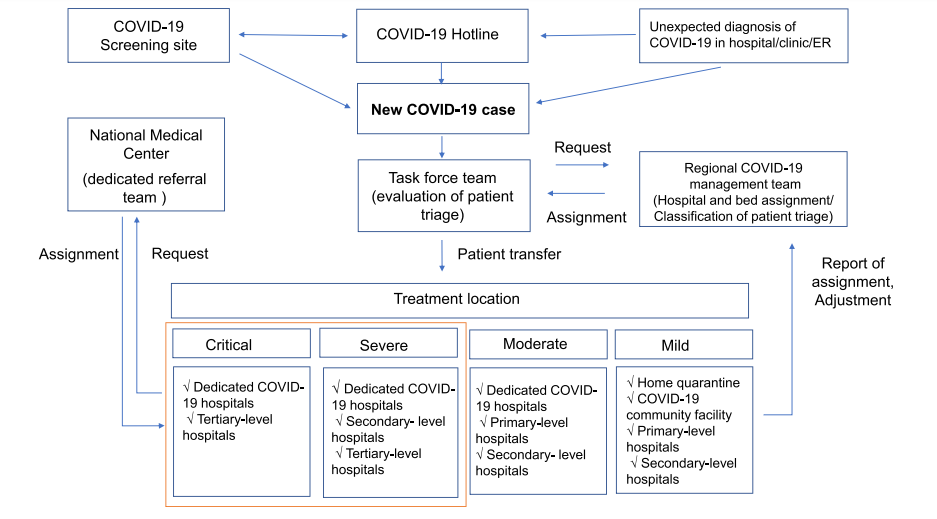

While all the countries have infection control and management guidelines in place, the key differentiating factor between countries that have successfully managed to prevent and control nosocomial infections (such as South Korea and Singapore) and those that have had high rates of infections in HCWs (such as Italy) is the early response in testing and stratifying patients thereby reducing the burden at the hospital level. South Korea19 conducts widespread testing in the community regardless of presentation of symptoms, thereby identifying asymptomatic, mild and moderate cases. COVID-19 management teams then stratify confirmed cases based on the level of their symptoms, with mild cases asked to self-isolate at home along with daily monitoring of symptoms, and other mild cases directed to community facilities, and severe and critical patients sent to hospitals (see figure 1). With such an organised response, hospital staff are well prepared for the incoming cases. While early testing and contact tracing reduces the burden of patients in the hospital, measures such as providing telehealth consultations for other medical areas and restricting visitors prevents overcrowding and enables effective management in this setting.

Figure 1. Stratification of hospital/room assignments for SARS-CoV2 in South Korea19

Overall, a major lesson that emerges is that while infection control guidelines have to be followed in hospital settings, other response measures are equally important to enable the effective implementation of these guidelines. These measures include (i) the need for preparedness (hospitals in Singapore and South Korea conduct pandemic drills and ensure that staff are well trained for such eventualities), (ii) financing public healthcare systems (investments in infrastructure and workforce), (iii) a coordinated response between federal and provincial governments (especially for procurement, stockpiling and ensuring timely PPE, ventilators and other materials), (iv) protection of HCWs (through training, PPE, testing, PPE, and support), (v) community surveillance through early and widespread testing and contact tracing, and (vi) use of virtual channels to provided non COVID-19 services during the outbreak.

3. UK government’s COVID-19 Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines

Point of entry

Symptomatic individuals are advised to consult NHS Inform online and phone 111 as the first point of contact,20 not their GP.21 In the case of any emergency admissions in the hospital, patients must be immediately identified as either i) asymptomatic; ii) symptomatic for COVID-19; iii) COVID+.22

Use of face mask

National guidelines recommend that symptomatic patients may wear a surgical face mask in clinical areas, common waiting areas or during transportation and where tolerable and appropriate.23 As of 15 June, all hospital staff in England will be expected to wear surgical masks, while all visitors and outpatients will be expected to wear face coverings at all times.24

Hand hygiene

All staff, patients and visitors should decontaminate their hands with alcohol-based hand rub when entering and leaving areas where patient care is being delivered. Hand hygiene must be performed immediately before every episode of direct patientcare and after any activity/task or contact that potentially results in hands becoming contaminated, including the removal of PPE, equipment decontamination and waste handling.25

Separation among zones of risk

Patients with suspected/possible COVID-19 need to be segregated, especially in admission/waiting and non-COVID areas. Any patient who subsequently tests positive or shows symptoms can be immediately isolated or managed in a COVID+ cohorted area.26 Hospitals across the country have been divided into zones to separate patients most likely infected with COVID-19 from those with other health problems.

Patient placement

Single rooms: Wherever possible, patients with possible or confirmed COVID-19 should be placed in single rooms. Where single/isolation rooms are in short supply, and cohorting is not yet considered possible (patient(s) awaiting laboratory confirmation), patients who have excessive cough and sputum production should be prioritised for single/isolation room placement. Single rooms in COVID-19 segregated areas should, wherever possible, be reserved for performing aerosol generating procedures (AGPs).

Cohorting: If a single/isolation room is not available, cohort possible or confirmed respiratory infected patients with other patients with possible or confirmed COVID-19. Use privacy curtains between the beds to minimise opportunities for close contact. Where possible, a designated self-contained area or wing of the healthcare facility should be used for the treatment and care of patients with COVID-19.

Negative pressure rooms: Special environmental controls, such as negative pressure isolation rooms, are not necessary to prevent the transmission of COVID-19. However, in the early stages where capacity allows, and in high risk settings, patients with possible or confirmed COVID-19 may be isolated in negative pressure rooms. Patients with suspected/confirmed COVID-19 should not be placed in positive pressure rooms.

Personal protective equipment (PPE)27

Conducting an aerosol generating procedure (AGP) on a possible/confirmed case outside a higher risk acute care area.

-

Single use gloves

-

Single use disposable fluid-repellent coverall/gown

-

Single use filtering face piece respirator

-

Single use eye/face protection (visor/goggles)

Working with a possible/confirmed case in higher risk acute care area

-

Single use gloves

-

Single use disposable plastic apron (sessional use full gowns for OT and labour wards)

-

Sessional use filtering face piece respirator

-

Sessional use eye/face protection (visor/goggles)

Working with a possible/confirmed case in other inpatient areas (other than higher risk acute areas), operating theatres and labour wards (no AGPs) and transferring patients

-

Single use

-

Single use disposable plastic apron

-

Single or sessional use fluid resistant surgical mask (risk assess)

-

Single or sessional eye/face protection (visor/goggles) (risk assess)

Providing inpatient care to any individual in the extremely vulnerable group undergoing shielding

-

Single use gloves

-

Single use disposable plastic apron

-

Single use surgical mask

Higher risk acute areas include ICU/HDUs; ED resuscitation areas; wards with non-invasive ventilation; operating theatres; endoscopy units for upper Respiratory, ENT or upper GI endoscopy; and other clinical areas where AGPs are regularly performed.

Testing

Staff

Symptomatic staff: If a member of staff develops symptoms of COVID-19 they should follow the stay at home guidance, and get tested as soon as possible. Staff should first tell their employer and then be tested in the first three days of the onset of symptoms - testing should not be undertaken after day five of symptoms. Those eligible for a test will be directed to the most appropriate place for testing including a local acute, mental health and community hospital trust/ local community venues/outreach testing centres.28 If the result is negative, the advice from Public Health England states that staff “can return to work when they are medically fit to do so, following discussion with their line manager and appropriate local risk assessment. Interpret negative results with caution together with clinical assessment.” If staff test positive for COVID-19, they can return to work after seven days, unless they still have symptoms other than a cough or loss of sense of smell/taste, in which case they must continue to self-isolate until they feel better.

Asymptomatic staff: Guidelines25 state that ‘additional available NHS testing capacity should be used to routinely and strategically test asymptomatic frontline staff as part of infection prevention and control measures. Local health systems should work together with their labs and regions to agree the use of available capacity.’

Patients

Emergency admissions: All patients should be tested on admission. For patients who test negative, a further single re-test should be conducted between 5-7 days after admission.

Elective admissions (including day surgery): Patients should isolate for 14 days prior to admission along with members of their household. As and when feasible, this should be supplemented with a pre-admission test (conducted a maximum of 72 hours in advance), allowing patients who test negative to be admitted with IPC and PPE requirements that are appropriate for someone who’s confirmed COVID status is negative.

Inpatients: Any inpatient who becomes symptomatic, who has not previously tested positive, should be immediately tested as per current practice.

Other day interventions: Testing and isolation to be determined locally, based on patient and procedural risk.

Discharge: All patients being discharged to a care home or a hospice should be tested up to 48 hours prior to discharge.

Team composition26

When there are sufficient levels of staff, a dedicated team of staff should be assigned to care for patients in isolation/cohort rooms/areas. Maintaining consistency in staff allocation where possible and reducing movement of staff between different pathways.

Visitors26

Visitors with COVID-19 symptoms must not enter the healthcare facility. Visitors who are symptomatic should be encouraged to leave and must not be permitted to enter areas where there are extremely vulnerable patients. Visiting may be suspended if considered appropriate depending on local circumstances and risk assessment. For e.g. Plymouth Hospitals Trust. has suspended visitors in its red and amber zones (suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19). All visitors entering a segregated/cohort area must be instructed on hand hygiene. They must not visit any other care area. Limiting entry points to a facility will help manage local restrictions.

Environmental decontamination

The main patient isolation room should be cleaned at least twice daily. Body fluid spills should be decontaminated promptly. Patient isolation rooms, cohort areas and clinical rooms must be decontaminated at least daily. Clinical rooms should also be decontaminated after clinical sessions for patients with possible/known pandemic COVID-19. Rooms/areas where PPE is removed must be decontaminated, ideally timed to coincide with periods immediately after PPE removal by groups of staff (at least twice daily). The increased frequency of decontamination/cleaning should be incorporated into the environmental decontamination schedules for all areas, including where there may be higher environmental contamination rates. Opportunities for cleaning of frequently touched surfaces multiple times (more than twice a day wherever possible) should be taken.

Non COVID-19 services

On 27 April, the government announced that the “restoration of other NHS services” will start from 28 April on a “hospital-by-hospital” basis. As of 14 May, NHS England stated that ‘over the coming weeks patients who need important planned procedures – including surgery – will begin to be scheduled for that care, with specialists prioritising those with the most urgent clinical need.29

In terms of planned and elective care, only patients who remain asymptomatic having isolated for 14 days prior to admission and, where feasible, tested negative prior to admission, should be admitted. In terms of outpatient services, only patients who are asymptomatic should attend these services, ensuring they can comply with normal social distancing requirements. Those requiring urgent and emergency care will continue to be tested on arrival and streamed accordingly, with services split to make the risk of picking up the virus in hospital as low as possible. Those attending emergency departments and other ‘walk-in’ services will be required to maintain social distancing, with trusts expected to make any adjustments necessary to allow this. Those requiring a long hospital stay will be continuously monitored for symptoms and re-tested between 5 and 7 days after admission, and those who are due to be discharged to a care home will be tested up to 48 hours before they are due to leave. Independent hospitals have been given the go-ahead to resume some private and elective surgery after NHS England triggered a ‘de-escalation’ clause in the historic contract signed with the sector in March to help tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.30 All opportunities for remote, multi-professional virtual consultations must be maximised. Most GP surgeries now offer online and video consultations.31

4. SARS-CoV-2 Infection prevention and control measures in South Korea, Singapore, New Zealand, Ireland and Australia

South Korea32

Point of entry

Triage is strengthened at the first point of entry to the emergency room at the hospital entrance for early case detection through measures like checklists. Checklists for patients with febrile respiratory symptoms, travel history or contact status with confirmed COVID-19 cases are prepared and circulated among HCW.

Patient placement

Patients with febrile respiratory symptoms are immediately placed in an isolated, negative pressure room. Suspected patients with febrile respiratory symptoms are separated from other patients even in the absence of symptoms.

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed patients

Critical care physicians wearing PPE take detailed history of patients with febrile respiratory symptoms, including contact with COVID-19 cases or travel history.

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed patients

Individuals with negative results and no evidence of pneumonia are transferred from the emergency room to cohort wards if they were stable, or to the cohort area of the ICU if they were unstable. In the case of evidence of atypical pneumonia and negative PCR results, individuals are transferred from the emergency room to a negative-pressure isolation room, and PCR tests are performed repeatedly.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

PPE, testing and daily monitoring of temperature are the three major practices followed for reducing the risk of infection among HCWs. Staff in charge of high-suspect COVID-19 cases, wear PPE, which includes N95 masks, face shields or goggles, long-sleeved gowns and gloves, and those performing aerosol-generating procedures. HCWs are regularly checked for their temperature and respiratory symptoms, and have access to testing.

Infrastructure

The hospital is divided in three zones based on risk stratification. First, the main hospital is maintained as the clean zone. Second, a separate temporary building (the moderate risk zone) is used for suspected COVID-19 cases, such as individuals with febrile respiratory symptoms without an obvious epidemiological link. A third zone, a separate area in the emergency department (high-risk zone) is used for patients at high risk of COVID-19 infection, such as individuals with febrile respiratory syndromes and a history of contact with confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Visitors and caregivers

The number of patient visitors and caregivers restricted; and all are required to adhere to personal hand hygiene standards and are given surgical masks to wear when visiting patients or healthcare workers.

Singapore33

Patient placement

Patients with COVID-19 are nursed in cohort rooms with three patients to a room, spaced at least w2 m apart, and partitions were placed between patient beds.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

Healthcare teams are kept small and segregated by type of patients: (i) suspect and confirmed cases of COVID-19 (ii) other patients. Teams are also organised to ensure there are enough HCWs if the outbreak worsens, and that they get enough rest. Cross-institution coverage by HCWs is suspended.

Tasks are stratified by risk of infection. Highest risk tasks (airway suctioning, intubation and bronchoscopy) warrant the donning of full PPE, including eye protection, disposable gown, gloves, and either an N95 mask or a powered air purifying respirator. Medium risk tasks, such as triaging Emergency Department patients at first presentation for fever and/or respiratory symptoms, requires a lower level of PPE.

Twice daily temperature monitoring of all HCWs is made mandatory. HCWs whose logged temperature readings are higher than 37.5 degree Celsius will be flagged up to the hospital’s clinical epidemiology team for further evaluation including testing.

Mealtimes for healthcare workers are staggered. Peer support programmes address the physical fatigue and psychological stress from regular donning and doffing of full PPE.

Physical distancing

In the general ward, shared communal facilities are closed, and patients are limited to one visitor at any time. Common areas such as waiting areas, pharmacies, patients are directed to keep 1m apart from one another, using visual cues to guide waiting and queuing in both seated and standing areas.

Visitors and caregivers

All visitors and outpatients undergo a questionnaire survey of travel and contact history, as well as thermal scanning for fever before they are allowed into the hospital premises.

Each inpatient is restricted to only 2 specified visitors through the period of hospitalization. Similarly, each outpatient is only allowed 1 accompanying person when attending the specialist outpatient clinic. No visitors are allowed in the respiratory surveillance ward.

Non-COVID-19 Medical Services

Didactic teaching and departmental meetings are conducted using video conferencing. Medical students are withdrawn from clinical attachments.

New Zealand34 35

Point of entry

Screening measures are in place for patients coming through to Emergency Department to see if they are symptomatic; and if they are coming for a respiratory illness then they go through a different pathway. Hospitals have begun treating all respiratory infection as potential COVID-19 cases, and such patients are provided with a surgical mask upon entry to the facility.

Patient placement

All patients who meet the case definition criteria for COVID-19 have to wear a surgical mask and are encouraged to follow cough etiquette and respiratory and hand hygiene. Cases under investigation, and probable cases are accommodated in a single room. If confirmed, they can be cohorted with other confirmed cases.

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed patients

Infection prevention and control precautions should apply for all suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19 and the patients should always wear a surgical mask and followed respiratory and hand hygiene.

In addition to standard precautions, contact and droplet precautions should be taken. When performing an aerosol generating procedure, apply airborne precautions including the use of an airborne infection isolation room (negative pressure room) where possible.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

HCWs must wear PPE for contact and droplet precautions. PPE includes long sleeve impervious gown, gloves, eye protection and surgical mask. PPE for contact and airborne precautions include long sleeve impervious gown, gloves, eye protection and particulate respirator (N95 mask).

General practitioners and healthcare workers with respiratory or influenza-like symptoms who are in close contact with patients (ie, less than 2 metres distance for more than 15 minutes) should be tested for COVID-19 and other potential causes of their illness.

Infrastructure

In response to staff fears, on May 8, the Waitakere Hospital instituted ward ‘bubbles’ segregating the hospital into different wards and promoting no cross-institutional coverage by HCW.

Visitors and caregivers

Family/Whānau (extended family) must wear a surgical mask and practice hand hygiene when supporting the patient during transfer to hospital and whilst being assessed in the emergency department.

Hospital visits are limited and restricted. Allowances of visits are determined by each district health board and are done so on a case-by-case basis. Screening of visitors will be done, and visitors may be refused entry. If approved, visits are done one-person at a time, are booked in advance, and require precautions such as hand hygiene and keeping a physical distance of 2 meters. When approved, visitors are required to wear PPE provided by the DHB.

Non-COVID-19 Medical Services

Elective surgeries may be postponed or rearranged. General practices are open, but appointments will be conducted online or by phone where possible.

Ireland36

Patient placement

Patients with COVID-19 should be cared for in single rooms with en suite facilities. They can also be cohorted together. Patients with suspected COVID-19 should not be cohorted with those confirmed positive.

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed patients

HCWs should perform aerosol generating procedures on confirmed patients in a negative pressure or neutral pressure room, ensuring that patients, visitors and other healthcare settings are not exposed.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

Designate small teams of HCWs caring for patients with possible or confirmed COVID-19 and review this allocation regularly to ensure that staff caring for COVID-19 patients do not care for patients without COVID-19 during the same shift.

Surgical masks should be worn by all HCWs for all encounters, of 15 minutes or more, with other HCW in the workplace where a distance of 2m cannot be maintained.

PPE for HCWs treating patients with COVID-19 include respiratory protection (surgical mask), Gloves, Long-sleeved gown (for high contact activities) /apron (for low contact activities), Eye protection as per risk assessment* (face shield or goggles) *where there is a risk of blood, body fluids, excretions or secretions (including respiratory secretions) splashing into the eyes. PPE for conducting aerosol generating procedures include PPE as above but an Filtering Face Piece 2 mask (rather than surgical mask) and long-sleeved gown.

At the start of each shift, all staff should be checked for symptoms of viral respiratory infections, such as cough, fever, shortness of breath or myalgia.If possible, designate extra catering support to staff working in cohort areas to minimise their need to travel in the facilities.

Physical distancing

Social interaction between HCWs who do not have to work together should be avoided.

Visitors and caregivers

Restrictions will be required on visitors, but allowance of specific scenarios such as compassionate and practical approach is required when making this assessment.

In labour wards, birth partners in whom there is no clinical suspicion of COVID-19 will be allowed to provide support to the mother in labour

When visiting patient’s rooms, visitors are required to perform hand hygiene and wear appropriate PPE.

Non-COVID-19 Medical Services

HCWs should try whenever possible to deliver care as remotely as possible (sometimes through the use of mobile telephones).

Australia37 38 39

Point of entry

All patients go through risk assessment to determine the level of PPE required if any. Patients with acute respiratory symptoms should wear surgical mask upon presentation to hospital. Suspected, probable and confirmed cases need to wear surgical masks.

Patient placement

Patients with acute respiratory symptoms must be placed in a single room with door closed, or in a separated closed area designated for suspected COVID-19 cases. Once the patient is isolated in a single room, they do not need to continue wearing a mask.

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed patients

If aerosol generating procedures have to be performed, the patient should be placed in a negative pressure room. For aerosol generating procedures performed on patients who are NOT suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19, P2 respirators are not necessary, i.e., a surgical mask is sufficient.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

Healthcare workers with influenza-like illness should not work while they are symptomatic. They should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 and undergo isolation pending results. Healthcare workers who are defined as close contacts should be treated as such.

When caring for patients (suspected and confirmed cases of COVID1-9), the PPE requirements for HCW depends on the task (i.e. routine care and aerosol generating procedures for patients with COVID-19) and setting (ICU, Wards outside the ICU, and the Emergency department).

In settings where the loss of the healthcare worker will have a significant impact on health services, an individual risk assessment should be conducted in collaboration with the Public Health Unit.

Physical distancing

Physical distancing measures in clinics, and wards between health workers and patients. Waiting room chairs are separated by greater than 1.5 meters. Direct communications between HCWs and patients conducted at a distance where practical, and if not, HWs wear appropriate PPE

Visitors and caregivers

Visitors to hospitals should be limited and restricted to essential circumstances. When entering hospitals, they should be trained and supervised when using PPE.

In the labour ward requirements, women’s partner or other support person may attend the delivery, but precautions are required to protect labour ward staff, such as performing hand hygiene and putting on a surgical mask when the individual is entering the hospital.

Italy40 41 42 43

Point of entry

The first evaluation is done by telephone or e-mail. In case of symptoms suggesting a possible COVID-19 infection, the patient is invited to stay home, isolated from the rest of the family. The GP monitors the evolution of the symptoms while avoiding as much direct contact as possible with these patients. In case of respiratory distress, a special hotline number has been set up to dispatch a team that can transfer the patient to the hospital. In the hospitals, separate areas for patients with COVID-19, are organised with a triage area equipped with mechanical ventilation equipment.

Patient placement

Dedicated patient transport and isolation pathways. Patients with respiratory symptoms, both suspected and confirmed cases tested and allocated to the appropriate cohort. Cohort ICUs set up for COVID-19 patients (areas separated from the rest of the ICU beds to minimise risk of in-hospital transmission).

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients

Isolated rooms with negative pressure to be identified for treatment of patients with COVID-19. However, reports from Italy found that critical care beds and negative pressure rooms ran out quickly in the first few weeks of the outbreak, since hospitals were overloaded by patients with acute respiratory failure, leading staff to use general wards with natural ventilation as a makeshift remedy.

Hospital infrastructure

Since the end of February, the hospitals in Northern Italy have been reorganised. Most of them have special areas for COVID-19 patients. Operating rooms turned into makeshift ICUs to create surge capacity. Hospitals have dedicated patient transport and isolation pathways.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

HCWs have to wear appropriate PPE based on routine case and other procedures for COVID-19 patients. One of the key safety restrictions is that of appropriate filtering face piece (FFP) masks. FFP2, N95 and FFP3 masks are recommended for the management of COVID‐19 patients, but the levels of protection for airway management in COVID‐19 patients adopted in most of hospitals in Italy are either second‐ or third‐level PPE, preferring the use of airborne‐level PPEs for critical care aerosol‐generating procedures, including tracheal intubation, bronchoscopy and ATI. So far, the outbreak‐related global PPE shortage has forced the use of lower‐protection PPEs for aerosol‐generating procedures.

Testing for HCWs is only available on display of severe symptoms.

Social distancing

Suspension of group activities and sharing of common spaces inside of the structure.

Visitors

For the entire duration of the emergency, visitors including family and acquaintances are prohibited from accessing the facility.

Other medical services

Cessation of elective surgery, semi-elective procedures postponed, with only emergency, trauma and selected oncological surgery proceeding. Most of the outpatient clinics have been closed and non-urgent visits are postponed, to make resources available for the most severe cases. Telemedicine consultations are being used for non-COVID-19 services where possible.

Germany44 45 46

Point of entry

If possible, tests in the outpatient and pre-inpatient areas should be carried out separately and if possible before further patient care / treatment. The tests should preferably be carried out in designated facilities outside of medical practices or outpatient clinics, which ensure the separation of patients with respiratory symptoms and other patients in order to be able to maintain regular care structures.

Patient placement

Cases, contacts and suspected cases of COVID-19, as well as non-cases, should be treated in three spatially and personnel-separate areas: COVID-19 area, suspected case area, NON-COVID-19 area. Patients with COVID-19 should only be seen and cared for by dedicated personnel.

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients

Patients should preferably be treated in isolation rooms ideally with a functional anteroom for donning and doffing PPE. As the epidemic/pandemic progresses, isolation of patients in cohorts is reasonable.

If SARS-CoV-2 is detected in patients or staff in an area that is not intended for COVID-19 patients, immediate action must be taken. This includes relocation of the case in the COVID1-9 area, use of mouse and noise protection for staff, setting up of an outbreak team, determination and allocating contacts to separate areas. Germany

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

General medical measures of wearing of medical mouth-nose protection by staff in all areas with possible patient contact and especially contact with patients with cold symptoms. In these situations, patients should also be treated with medical mouth-nose protection. All other basic hygiene measures must also be observed. Direct contact of all kinds should be reduced in medical facilities.

Separation of personnel with strict assignment to individual areas in which they should be allowed to treat either COVID-19 or non COVID-19 patients. Wherever possible, work should be carried out in permanent teams, so that in the event of a new infection, as few contacts as possible are available among the staff.

Testing and subsequent resuming of work for HCWs is based on whether there is a relevant shortage of staff.

In the first scenario, where there is no shortage, HCWs who have symptoms can stay away from patient care and resume work after being free from symptoms for 48 hours, with a test conducted if possible. In this scenario, if HCWs have SARS-CoV2, then they cannot attend to patients and can resume work only after 48 hours of being free from symptoms and after negative PCR from 2 simultaneous oro- and nasopharyngeal swabs. In the second scenario, where there is a shortage of staff, HCWs with symptoms can give patient care but have to wear mouth and nose protection at all times and test for SARS-CoV2. If the test results are positive, then they can resume care for non-COVID-19 patients after being symptom-free for at least 48 hours and negative PCR from 2 simultaneous oro- and nasopharyngeal swabs. The health status of the staff should be regularly monitored and, if necessary, a diagnostic clarification should be carried out. Employees with acute respiratory diseases should stay at home.

Visitors

Restrictions to visits by family and friends. If permitted, visits should be kept to a minimum and time limited. Protective measures are required by visitors including: maintaining a distance of at least 1.5 m from the patient, wearing protective gowns and close-fitting, multi-layer mouth and nose protection as well as using hand sanitizer when leaving the patient’s room.

Other medical services

Even outside direct care of COVID-19 patients, the general wearing of PPE for all staff in direct contact to particularly vulnerable patients.

Denmark47 48

Point of entry

People with mild respiratory symptoms who may suspect COVID-19 are generally encouraged to stay home, as well as keep distance, and can additionally by phone contact the GP and test for SARS-CoV-2 as recommended.

When examining COVID-19 in a hospital, or in a special COVID-19 regional assessment unit (‘Fever clinic’), a clinical assessment of the patient, including an assessment of symptoms, followed by testing as required.

Patient placement

Suspected COVID-19 patients are placed in a single room or behind room separation that is visited only by designated and necessary staff. Isolation can be done as cohort isolation, where patients with verified same infectious disease and micro-organism gene type

Treatment response for suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients

In direct patient contact, personnel should wear protective equipment in the form of gloves, liquid-repellent, long-sleeved disposable coat, surgical mask and visor / goggles. FFP2 or FFP3 mask is used in high-risk procedures. Disposable equipment should be used as far as possible for patient care.

If intensive treatment is needed, including mechanical ventilation (respirator), this can be taken care of head of the team. Patients are hospitalised in isolation and managed according to droplet infection guidelines.

Hospital infrastructure

Separate COVID-19 cohort isolation wards have been set up using existing wards, and the available number of intensive care beds have been tripled.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

Healthy employees as well as employees with symptoms that are not compatible with COVID19 can go to work as normal. Upon presentation of SARS-CoV2 like symptoms, employees should get tested, leave the workplace immediately and cannot care for suspected or confirmed cases. Employees can be tested for mild symptoms and can resume work after negative test results. If employees test positive, then they can resume patient care after 48 hours of being symptom-free. For employees at high-risk, they must have been tested again 48 hours after symptom cessation, and if negative, reassessment should be performed after another 24 hours. If this test is also negative, the employee can resume work. Consideration should be given to whether the recovered employee can be relocated to a less sensitive work area, from becoming symptom-free for 48 hours and until there are 2 x negative tests available.

If a situation arises, where the test capacity does not match the need for testing for SARS-CoV-2, testing must be prioritized to (i) patients with moderate to severe symptoms who are hospitalised or are already admitted in the hospital, (ii) employees who perform functions in healthcare, the elderly, efforts for particularly vulnerable groups in the social field, or in other very key functions in society, (iii) citizens and employees of care centers, residences, closed institutions and other settings where it can be difficult to ensure isolation, distance, hygiene (iv) particularly vulnerable individuals.

In Nordsjællands Hospital, a 600-bed facility situated north of Copenhagen, apart from PPE provision and creating new workflows, healthcare workers are offered a psychological intervention to address fear, anxiety and stress.

Other medical services

Hospital system will prioritise those who are critically ill – some treatments will need to be postponed, such as non-emergency operations and other major non-critical interventions. Fewer meetings in practices or clinics. At risk patients should be offered telephone or video consultations.

Sweden49 50 51 52

Point of entry

A triage tent is set up at the entrance of the hospital. Individuals with no COVID-19 symptoms are sent directly to the emergency room or home without entering the triage tent.

Patient placement

Suspected COVID-19 patients with no serious symptoms referred to isolation with instructions on self-care. While suspected COVID-19 patients - with general symptoms, where emergency visits and possibly in-patient care is necessary are allocated to a separate area in the hospital.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

The healthcare services in Sweden prioritise testing for hospitalised patients and health or elderly care personnel with suspected COVID-19.

Despite the policy on testing HCW only symptoms, the Linköping University hospital decided to test all staff in the department after having had some patients with COVID-19. It turned out half (50) of the staff tested positive for the coronavirus, and between five and ten of them did not have any symptoms at all, or only a little headache or a slight sniffle.

In the Karolinska University Hospital, HCWs have gone up to working 12.5 hours, splitting the day into two shifts instead of three.

Visitors

Visitors are restricted.

Norway53 54

Point of entry

Individuals with symptoms are encouraged to contact the GP as the first point of contact.

Reducing the risk of infection among healthcare workers

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health recommends that tests for health-care workers should be performed for SARS-CoV-2 on showing acute respiratory tract infections with fever, cough or breathing difficulties.

Visitors

Restrictions on visitors to all the country’s health institutions and the introduction of entry control.

Other medical services

E-consultation or video consultation options should be provided.

CASES: Two hospitals that have prevented nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infections among health workers and patients

Samsung Medical Centre in South Korea55

Samsung Medical Center, a 2000-bed tertiary hospital in Seoul with 9,000 staff, has adopted a rigorous infection control strategy which has led to zero infections in staff and secondary infections in patients as of early May. All hospital visitors are thoroughly screened for risk of SARS-CoV-2 with questionnaires, scanned with thermal cameras, and required to wear masks prior to entering the building. Advanced screening of patients and use of telemedicine limit unnecessary patient encounters. Designated COVID-19 screening, treatment, and quarantine areas are separated from the rest of the hospital. COVID-19 units are staffed by only dedicated core clinical teams with special training who live in hospital accommodations during two-week shifts and then are quarantined for one week and only allowed to return to the care of non COVID-19 patients after a negative COVID-19 test. Health staff wear full body suits with powered air purifying respirators while caring for COVID-19 patients, particularly for critically ill patients requiring high-risk procedures. Strict social distancing is enforced throughout the hospital, in particular the cafeteria, which is considered a particularly high-risk area for disease transmission among staff. All staff are required to wear surgical masks in the hospital, and N95 masks are required when seeing any patient with respiratory symptoms and while performing high-risk procedures regardless of the patient’s COVID-19 status.

Cotugno Hospital in Italy56

The Cotugno Hospital, a specialist infectious diseases facility in Naples, only treats COVID-19 patients, and has managed zero infections among health staff as of April. Staff protection at the hospital goes beyond standard WHO recommendations, as they wear thick waterproof suits and those inside the treatment rooms with patients communicate through a window to those outside. Medicines are passed through a compartment. The ICU is divided into two zones. The first zone is a sub-intensive unit with patients that are recovering or haven’t deteriorated, while the second zone houses the critical patients, and different care teams are allocated to these two zones. A red and white tape marks the line that cannot be crossed. Clean area nurses and doctors assist infected area staff across the line. They keep the two absolutely separate. Since this is a specialist hospital that has been dealing with infectious diseases, the staff are well trained and have the knowledge and experience of implementing infection control measures including how to separate areas and wear and remove PPE. It is important to note that since the COVID-19 outbreak first started in the north of Italy, this hospital had more time to prepare for the emergency, and had more technological tools, devices and trained staff that strictly followed protocols.

5. Footnotes and References

-

Mantovani, C. (2020). Over 90,000 health workers infected with COVID-19 worldwide: nurses group. Reuters. https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-nurses/over-90000-health-workers-infected-with-COVID-19-worldwide-nurses-group-idUKKBN22I1XH ↩

-

Quinn, B. (2020). Number of key workers getting COVID-19 overtakes positive tests in hospitals. The Guardian. Published on May 5, 2020.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/05/number-of-key-workers-getting-COVID-19-overtakes-positive-tests-in-hospitals ↩

-

Henegan, C., Oke, J. and Jefferson, T. (2020) COVID-19: how many healthcare workers are infected? Centre for Evidence Based Medicine. Published on 17 April 2020. Available at: https://www.cebm.net/COVID-19/COVID-19-how-many-healthcare-workers-are-infected/ ↩

-

Cook, T., Kursumovic, E, and Lennane, S. Exclusive: deaths of NHS staff from COVID-19 analysed. Health Services Journal. HSJ. Published on 22 April 2020. https://www.hsj.co.uk/exclusive-deaths-of-nhs-staff-from-COVID-19-analysed/7027471.article ↩

-

The Lancet (2020) COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. The Lancet, 2020. 395 (10228), p. 22. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30644-9/fulltext ↩

-

The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team (2020) The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) — China, 2020. China CDC Weekly, 2020. Available at: http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51 ↩

-

Wang D. et al. (2020). Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA; doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 ↩

-

Guan W-J et al. (2020). Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. New Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 28; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 ↩

-

Robert Kock Institute (2020) Daily Situation Report. Published 16 May 2020. Available at: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/2020-05-16-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile ↩

-

Jewett, C. and Szabo, L. (2020). Coronavirus is killing far more US health workers than official data suggests. The Guardian. Published April 15, 2020. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/15/coronavirus-us-health-care-worker-death-toll-higher-official-data-suggests ↩

-

Hunter, E., Price, D., Murphy, E., et al. (2020) First experience of COVID-19 screening of health-care workers in England. Lancet 2020; 395(10234):e77-e78; Keeley, A., Evans, C., Colton, H. et al. (2020) Roll-out of SARS-CoV-2 testing for healthcare workers at a large NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(14):2000433; Treibel, T., Manisty, C., Burton, M., McKnight, A., Lambourne, J., Augusto, J., Couto-Parada, X., Cutino-Moguel, T., Noursadeghi, M., Moon, J. (2020) COVID-19: PCR screening of asymptomatic healthcare workers at London hospital. Lancet 2020; 395: 1608-1609; Rivett, L., Sridhar, S., Sparkes, D. et al (2020) Screening of healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 highlights the role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. eLife 2020;9:e58728; Klaber, B. (2020) Developing a COVID-19 testing strategy with local, national and global impact. Imperial College NHS Trust. https://www.imperial.nhs.uk/about-us/blog/developing-a-COVID-19-testing-strategy ↩

-

National Audit Office (2020) Readying the NHS and adult social care in England for COVID-19. 12 June 2020. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/readying-the-nhs-and-adult-social-care-in-england-for-COVID-19/ ↩

-

Department of Health and Social Care (2020) COVID-19: Our Action Plan for Adult Social Care. 15 April 2020. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879639/COVID-19-adult-social-care-action-plan.pdf ↩

-

Sirna, L., Muñoz Ratto, H., and Talmazan, Y. (2020). Medical workers in Spain and Italy ‘overloaded’ as more of them catch coronavirus. NBC news. Published on March 30. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/medical-workers-spain-italy-overloaded-more-them-catch-coronavirus-n1170721 ↩

-

Li, R. and Chung, D. (2020). The Role of Hospital Infection Control in Flattening The COVID-19 Curve: Lessons From South Korea. Health Affairs. Published on May 15. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200511.415767/full/ ↩

-

Gawande, A. (2020). Keeping the Coronavirus from Infecting Health-Care Workers. The New Yorker. Published March 21. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/keeping-the-coronavirus-from-infecting-health-care-workers ↩

-

Robert Koch Institute. (2020). Guidelines for prevention and management of SARS-CoV2 in healthcare facilities. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/nCoV_node.html ↩

-

Quang Thai P., (2020). Addressing COVID-19 in Vietnam: Progress to date and future priorities. Usher Institute Webinars. May 13 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wibA34w8Xyo&feature=youtu.be ↩

-

Her, M. (2020). Repurposing and reshaping of hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. One Health 10 (2020) 100137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100137 ↩ ↩2

-

NHS (2020) What to do if coronavirus symptoms get worse. 17 June 2020. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/self-isolation-and-treatment/what-to-do-if-symptoms-get-worse/ ↩

-

Health Protection Scotland (2020) Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Guidance for secondary care Management of possible/confirmed COVID-19patients presenting to secondary care. 29 May 2020. Available at: https://hpspubsrepo.blob.core.windows.net/hps-website/nss/2936/documents/1_covid-19-guidance-for-secondary-care.pdf ↩

-

NHS (2020) Operating framework for urgent and planned services in hospital settings during COVID-19. 14 May 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/05/Operating-framework-for-urgent-and-planned-services-within-hospitals.pdf ↩

-

Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), Public Health Wales (PHW), Public Health Agency (PHA) Northern Ireland, Health Protection Scotland (HPS), Public Health Scotland, Public Health England and NHS England (2020) COVID-19: infection prevention and control guidance. 18 June 2020. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886668/COVID-19_Infection_prevention_and_control_guidance_complete.pdf ↩

-

Public Health England (2020) New government recommendations for England NHS hospital trusts and private hospital providers. 18 June 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/new-government-recommendations-for-england-nhs-hospital-trusts-and-private-hospital-providers ↩

-

SAGE (2020) Dynamic CO-CIN report to SAGE and NERVTAG (1 April 2020). Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886424/s0096-co-cin-report-010420-sage22.pdf ↩ ↩2

-

Office for National Statistics (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey pilot: 5 June 2020: Office for National Statistics. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/5june2020/pdf ↩ ↩2

-

NHS (2020) Recommended PPE for healthcare workers by secondary care inpatient clinical setting, NHS and independent sector. 15 May 2020. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886707/T1_poster_Recommended_PPE_for_healthcare_workers_by_secondary_care_clinical_context.pdf ↩

-

NHS (2020) How do NHS employees get a test for COVID-19? 29 April 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/04/COVID-19-test-for-Staff-29-04-20.pdf ↩

-

NHS England (2020) NHS roadmap to safely bring back routine operations. 14 May 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2020/05/nhs-roadmap/ ↩

-

Davies, M. (2020) Private hospitals can resume some electives as COVID-19 surge eases. LaingBusson. 19 May 2020. Available at: https://www.laingbuissonnews.com/healthcare-markets-content/news-healthcare-markets-content/private-hospitals-can-resume-some-electives-as-COVID-19-surge-eases/ ↩

-

NHS (2020) GP online consultations. 7 April 2020. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/using-the-nhs/nhs-services/gps/gp-online-and-video-consultations/ ↩

-

Kim YJ et al. (2020) Preparedness for COVID-19 infection prevention in Korea: a single-centre experience, Journal of Hospital Infection. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.018 ↩

-

Hoe GAN W, Wah LIM J, KOH D (2020) Preventing intra-hospital infection and transmission of COVID-19 in healthcare workers, Safety and Health at Work, doi: 10.1016/ j.shaw.2020.03.001.; Government of Singapore. DORSCON (2020) What do the different DORSCON levels mean? Published 6 February 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.sg/article/what-do-the-different-dorscon-levels-mean ↩

-

Ministry of Health, Government of New Zealand (2020) Infection prevention and control procedures for DHB acute care hospitals. Available at: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/pages/dhb_acute_care_hospitals_advice_21_april_.pdf; ↩

-

Newsroom (2020) Waitakere: Fifth nurse infected - one seriously ill. Newsroom, May 8, 2020. Available at: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2020/05/08/1163674/waitakere-nurse-seriously-ill-in-hospital ↩

-

HPSC (2020) Infection Prevention and Control Precautions for Possible or Confirmed COVID-19 in a Pandemic Setting. Health Protection Surveillance Centre. Ireland. 8 May 2020. Available at: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/respiratory/coronavirus/novelcoronavirus/guidance/infectionpreventionandcontrolguidance/Interim%20Infection%20Prevention%20and%20Control%20Precautions%20for%20Possible%20or%20Confirmed%20COVID-19%20in%20a%20Pandemic%20Setting.pdf ↩

-

Queensland Government (2020) Interim infection prevention and control guidelines for the management of COVID-19 in healthcare settings. Published 11 May 2020. Available at: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0038/939656/qh-COVID-19-Infection-control-guidelines.pdf; ↩

-

Australian Government (2020) Guidance on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak. 24 April 2020. Australian Government, Department of Health. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/04/guidance-on-the-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-ppe-in-hospitals-during-the-covid-19-outbreak.pdf ↩

-

Australian Government (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units, Australian Government, Department of Health. 13 May 2020. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cdna-song-novel-coronavirus.htm ↩

-

Rosenbaum, L. (2020). Facing COVID-19 in Italy — Ethics, Logistics, and Therapeutics on the Epidemic’s Front Line. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1873-1875; Ovadia, D. (2020). COVID-19: What Can the World Learn From Italy? Medscape. Published March 13, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/926777#vp_4; ↩

-

Ministero della Salut (2020). Indicazioni ad interim per la prevenzione e il controllo dell’infezione da SARS-COV-2 in strutture residenziali sociosanitarie. Published on April 18, 2020. Available at: http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=73875&parte=1%20&serie=null ↩

-

Sorbello, M. et al. (2020). The Italian coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: recommendations from clinical practice. Anaesthesia. doi: 10.1111/anae.15049 ↩

-

Nava, S., Tonelli, R., Clini, E. (2020). An Italian sacrifice to COVID-19 epidemic. European Respiratory Journal. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01445-2020 ↩

-

Schwierzeck, V., König, J., Kühn, J., Mellmann, A., Correa-Martínez, C., Omran, H., Konrad, M., Kaiser, T., Kampmeier, S. (2020) First reported nosocomial outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in a pediatric dialysis unit, Clinical Infectious Diseases, ciaa491, doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa491 ↩

-

Robert Koch Institute. (2020). Guidelines for prevention and management of SARS-CoV2 in healthcare facilities. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/nCoV_node.html ↩

-

Sundhedsstyrelsen (National Board of Health) (2020) Guidelines for handling COVID-19 in healthcare. Translated from Danish. Available at: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2020/Corona/Retningslinjer/Retningslinjer-for-haandtering-af-COVID-19.ashx?la=da&hash=BE6BE868AA53E335DD6F7003AD134D5E5D8AD122 ↩

-

Olesen, B. et al (2020). Infection prevention partners up with psychology in a Danish Hospital successfully addressing staffs fear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Hospital Infection. Available at: https://www.journalofhospitalinfection.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0195-6701%2820%2930208-5 ↩

-

The Local (2020) Here’s what healthcare workers in Sweden are saying abou the coronavirus. Published 6 April 2020. Available at: https://www.thelocal.se/20200406/heres-what-healthcare-workers-in-sweden-are-saying-about-the-coronavirus; Medpage Today(2020 Are Stockholm’s hospitals about to break? Published 1 May 2020. Available at: https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/COVID19/86256 ↩

-

National Board of Health and Welfare, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Sweden (2020) Emergency and outpatient care: Support for triage. March 2020. Available at: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/kunskapsstod/COVID19-yttre-triage-skiss.pdf ↩

-

Public Health Agency of Sweden (2020). Testing, vaccination, and treatment. Published May 13, 2020. Available at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/communicable-disease-control/COVID-19/testing-vaccination-and-treatment/ ↩

-

Radio Sweden (2020) Healthcare staff without symptoms tested positive for COVID-19. Published on April 8. Available at: https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2054&artikel=7448444 ↩

-

Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2020) Test criteria for coronavirus. Updated on May 7. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/en/op/novel-coronavirus-facts-advice/advice-to-health-personnel/test-criteria-for-coronavirus/?term=&h=1 ↩

-

Forland, F. (2020) The Politics of Pandemics: Norway’s response to COVID-19. Webinar by Frode Forland, Specialist Director at the Norwegian Public Health Institute. Published on May 8. Available at:https://www.sum.uio.no/english/research/news-and-events/events/guest-lectures-seminars/2019/Norway-COVID-response ↩

-

Li, R. and Chung, D. (2020). The Role Of Hospital Infection Control In Flattening The COVID-19 Curve: Lessons From South Korea. Health Affairs. Published on May 15. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200511.415767/full/ ↩

-

Ramsay, S. (2020). Coronavirus: The Italian COVID-19 hospital where no medics have been infected. Sky News. Published April 1. Available at: https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-the-italian-COVID-19-hospital-where-no-medics-have-been-infected-11966344 ↩